On my new daily commute to the Intensive Care Unit—my new coworking, no co-living space. Death is all around—nurses and doctors on 12-hour shifts. Next of kin are welcome to stay unless they are performing more serious work. Why? Part of me fears the worst. Every eventuality is terrible. Youth, gone. This is the reality.

I slip into could-have, should-have, would-haves. I snap out of it. Baba fantasizes about me living with him. Tells me that 30% of adults live with their parents. That someone he knows has built a separate shed to live with them. Communal vs. individualism. I begin to agitate. I find myself explaining—I am forty years old, and my career has evaporated. I have a home in a fascist country where I cannot breathe because of the rise of racism and oppression. I don’t know what to say or do.

My phone tells me my step count has changed. Back in the suburbs, I began exercising daily—pull-ups at the park and PT at sunrise. I must live.

Mama must live.

She’s waking up now. They even removed her endotracheal tube this morning. The euphoria died quickly, replaced by a new depth of depression.

Will she be stuck like this? Will she regain her speech? Will she suffer from permanent aphasia?

She seems to favor her left side. She looks to the left, squeezes her left hand, and wiggles her left foot.

Baba says, "She keeps looking at the exit. Maybe she wants to leave." The nurses entertain him; they sympathize.

When the physiotherapist arrives, she suddenly raises her arm, an accusatory finger, eyes widening.

I tend to have this effect on people, she humors. She has so much phlegm, we need her to cough to keep it from drowning her lungs.

She doesn’t like to cough. She doesn’t like the tubes. At least her tongue seems to work. She resists.

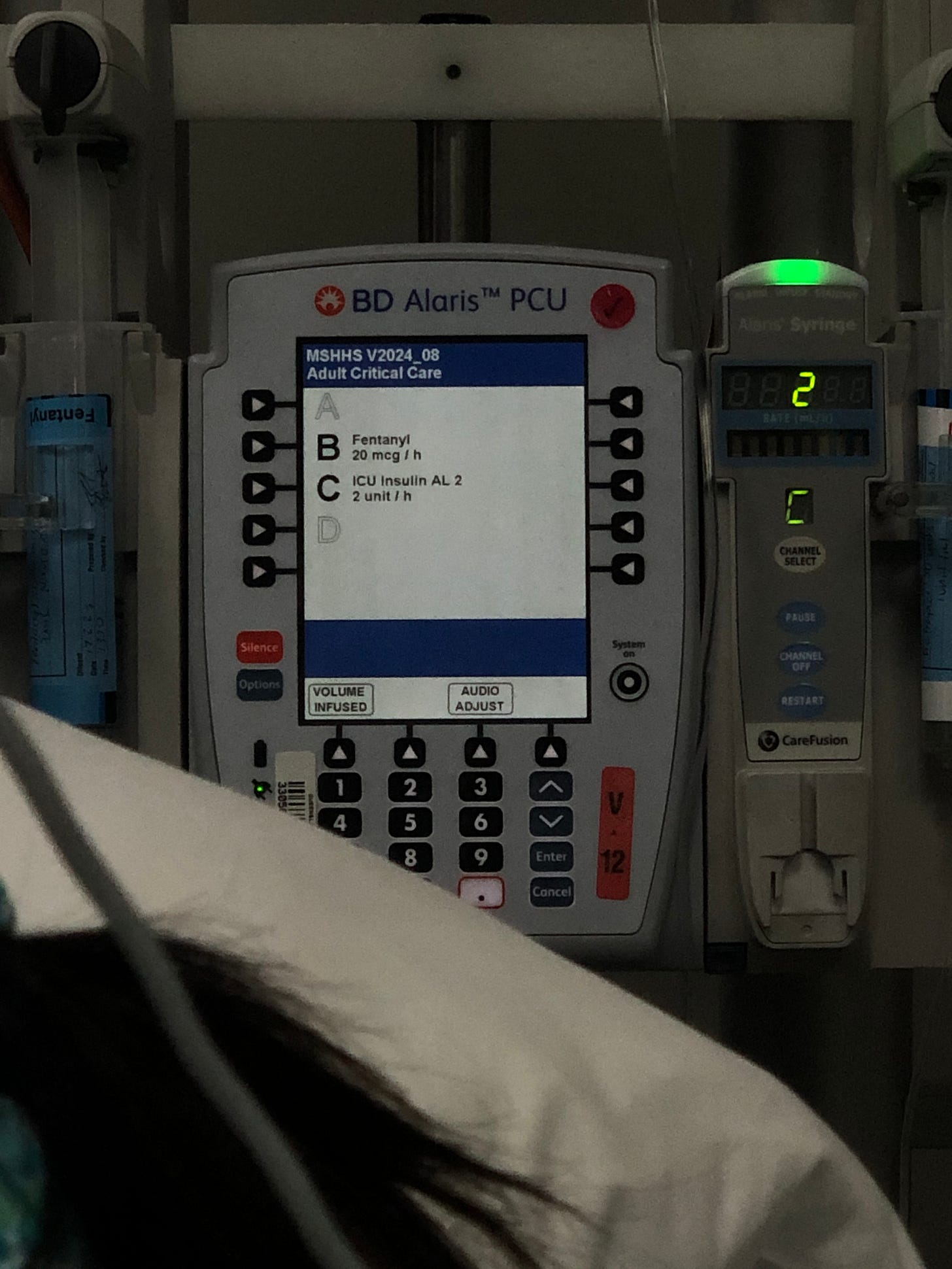

She has had two days of fentanyl—eighty to a hundred times stronger than morphine. Would I want to be woken back into this grim world?

Would I fight? Yes, I must live. What imperative keeps me going?

I look at her gaze—is there recognition?

She squeezes my hand. Baba and I try to convince ourselves, the nurses—this is recognition. Some nurses are less confident than others. Are they just twitches or tics? Before the endotracheal removal, they repeated that she must be able to receive commands.

To receive commands is a prerequisite to life, more primal than giving commands. Is that the meaning of life?

Every day, a woman with Tourette’s arrives at the café for lunch. What do we decide to acknowledge, and what do we ignore?

There are moments when Baba starts repeating himself, on and on—the same obsessions. But I wonder—who will miss our peculiarities when they disappear?

I try to negotiate, to talk to her as if we were equals, as if we understood.

But do we?

She has every connector available—a chest tube siphons excess fluid. A nasogastric tube was threaded sustenance into her stomach. Intravenous lines dripping a cocktail of sedatives, vasopressors, and electrolytes. A ventilator pushes measured breaths through an endotracheal tube. Her body is a circuit board of medical intervention, each line a negotiation between survival and death.

The look of recognition in her eyes—in and out of consciousness. How much capacity remains?

Baba reveals his anger and panic—the frustration of communication. He also discusses the difficulty of understanding Indian call center operators, the decrease in interest rates, and the price of fruits at the market. The time left at the parking meter.

Dignity is not cheap. It requires energy and patience. Not something we can always afford.

I remember the horror of being treated without dignity and told to assimilate. Traveling requires coming home, but what if one is lost? Where has our language gone?

When I close my eyes, exhausted, I feel her hands resting in mine. I slide in, fitting neatly. She listens, and I squeeze back. We communicate slowly, speaking, listening, through squeezes.

Throughout the day, I clutch my phone. When I’m not at her bedside, I am holding her hands. I feel her pulse. 八脉 (Ba Mai) — the Chinese medicine way. Not just beats per minute, but a profile.

At times, it flutters—faint. When someone drops a bottle, a huge noise startles her. Her pulse resurges—strong. Her eyes widen.

On the other hand, I clutch my phone. My friends are on the other side of the world. People I know. People I don’t. A semblance of responses.

With Mama, it is the opposite. As much as I can be by her side, how much recognition varies.

What makes a person a person?

What happens to the friends who choose to disconnect? Unable to continue, unable to face the unbearable?

The relationships where communication no longer works?

Today, most people are just a click away. Sure, they might not answer. But who speaks? Who listens?

I feel her pulse. Her 脉 (Mai). Her gaze.

As I doze off to a sweet sleep on the bus, the memory of her touch lingers in my hand.