Preface

A lot happens in a month.

The following essay I wrote on October 1, 2023, as a reflection for a class of Loren Dent’s Introduction to Trauma course at the Brooklyn Institute for Social Research. This was before the interview I made with Professors Lara Sheehi and Stephen Sheehi on Psychoanalysis Under Occupation, prior to October 7 and prior to Australians deciding “No” to “The Question,” which asked the voters of Australia whether to alter the Constitution to recognize the First Peoples of Australia by establishing an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice.

In spite of everything—as the death toll rises, as disagreements continue, as the misinformation pours, as the protests continue despite government illegal attempts to silence the people, the growing dissent amongst people—I wish to share with you this reflection.

Stef Craps published in 2014, Beyond Eurocentrism: Trauma Theory in the Global Age which examines trauma theory and presents a methodology for examining books, movies, and cultures to gain insights into real-world issues such as trauma (Craps, 2014). Through this lens, one can better understand how trauma impacts individuals or even entire cultures.

While Cathy Caruth argues that examining trauma can offer profound insights into history and serve as a unifying factor among diverse cultures, Craps (2014) raises concerns about the field's Western-centric focus. According to Craps, Trauma Theory primarily hinges on Western paradigms, thereby neglecting non-Western perspectives and potentially making assumptions that aren't universally applicable (Craps, 2014, p. 51). This lack of inclusivity can result in significant blind spots despite the good intentions behind Trauma Theory.

Through specific aesthetics, like fragmented storytelling, it can capture what the experience of trauma is like. But this is limiting because it mostly includes a Western perspective and ignores how different cultures might talk and show trauma.

In the case of the film Hiroshima, Mon Amour (Duras & Resnais, 1959), Caruth points out how the movie shows an understanding of trauma can help cultures connect (Craps, 2014, p. 47).

Hiroshima, Mon Amour is also a rare category involving a romantic relationship between a white woman and an Asian man. I tried to do a film study of 100 Asian men in white cinema. Unfortunately, I failed to find enough available films for this project with this interracial dynamic due to a history of anti-miscegenation and racism in cinema.

Despite Hiroshima, Mon Amour is one of the most notable films about cross-cultural love themes. The film mainly discusses the trauma of the French woman. Craps (2014) sheds light on how Cathy Caruth misses some crucial points.

Here, the Japanese man becomes a plot container, which allows the French woman to reminisce about her traumatic memories. The Japanese man of Hiroshima is reduced to nothing more than a plot device.

I’m curious how a Lacanian interpretation here may provide a different view—the more significant trauma, namely the site of the Hiroshima nuclear dropping, is a horror too overwhelming that the only way to even touch on this Lacanian Real (referring to everything that resists symbolization; it's what can't be put into words, like overwhelming emotions or experiences) is to circumvent it entirely through the focus on the traumatic memories of the French actress.

Another example is Picnic at Hanging Rock, directed by Peter Weir and released in 1975 (Weir, 1975). It is a historical fiction set in 1900 about a group of female students at an Australian girls’ boarding school who vanished at Hanging Rock on a Valentine’s Day picnic. The film is about how the disappearances affect the school and local community.

After the film’s release, Australian audiences’ most commonly asked question was whether or not the film was based on actual events.

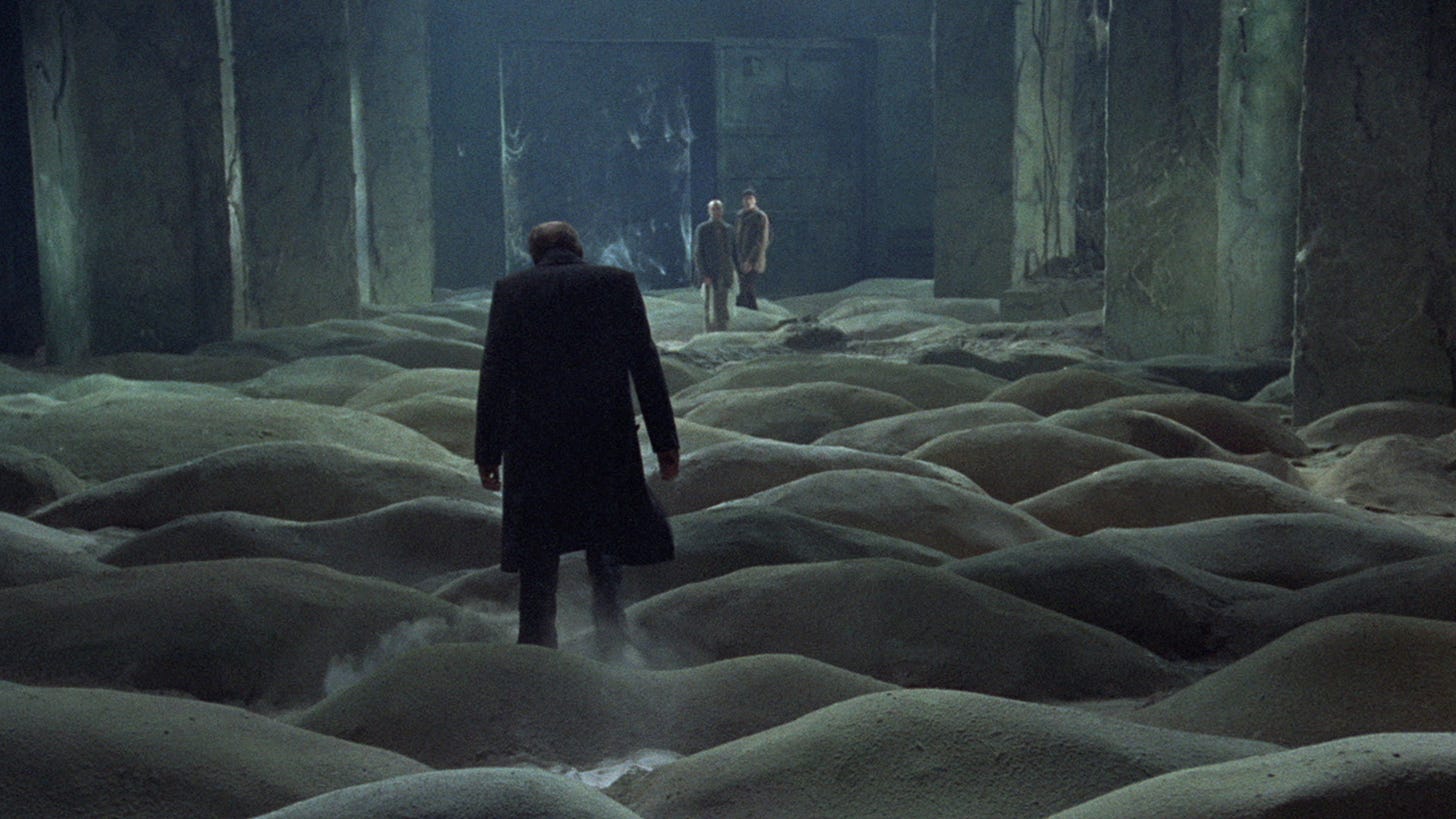

The film was recommended by Slavoj Žižek, who compared it to Tarkovsky’s 1979 film, The Stalker. The film discusses the Zone, which can be compared to the ineffable experiences that defy easy descriptions or understanding (CriterionCollection, 2014). It also serves as a function that disrupts the regular order of things. Physical laws don’t hold in the Zone, as in the Real, usual Symbolic and Imaginary constructions break down. In Tarkovsky’s Zone, the Room promises to fulfill one’s deepest, often unconscious desires (Tarkovsky, 1979).

This Zone of Tarkovsky is similar to the Hanging Rock in Weir’s film, where virginal young girls, all dressed in white, are led on Valentine’s Day—a subtle variation on the King Kong theme to this mythical place. In the film, the girls speak about how “quiet the place is” and that “there’s no one in sight” (Weir, 1975).

What this film shares with Hiroshima, Mon Amour is how the Lacanian Real can be approached. It would perhaps be too vulgar and impossible to speak about the horrors of Hiroshima, just as the inability to speak on the horrors of the Stolen Generation in Australia, where white colonizing settlers kidnapped, raped and genocided the indigenous population. The Stolen Generation project was justified by the colonizing people based on the idea of social engineering to assimilate the First Nations people in what is now referred to as Australia, as Mary Terszak recounts in her book, Orphaned by the Colour of My Skin, A Stolen Generation Story, which recounts her autobiographical journals as well as federal public policies during that time (Terszak, 2008).

The story in Picnic at Hanging Rock was set in 1900, the year before the establishment of the nation of Australia, 1901. The film itself was released in the year in which The Commonwealth Government passed the Racial Discrimination Act of 1975, and 1976 was the year of the passing of the Aboriginal Land Rights, which provides recognition of Aboriginal land ownership and grants land rights to 11,000 Aboriginal people and enabling other Aboriginals to lodge a claim for recognition of traditional ownership of their lands (Central Land Council, Australia, 2020).

This leads me to the question, how does the colonizer approach guilt and shame regarding trauma beyond 9/11 and the holocaust?

One could employ the notion of a Universal Human Experience, considered an a priori concept, to foster cross-cultural understanding. However, this raises the question: how would we address the unique cultural nuances or possibilities outside one culture’s realm of possibility?

A global standardization approach is quickly positioned to dismiss the value of indigenous or localized treatment methods. As for Freud wanting to simplify, to ensure the survivability of Psychoanalysis, to push it into the realm of hard sciences, have thinkers like Cathy Caruth taken for granted that trauma is seen as evidently universal as water running downhill?

But to take on a cultural relativist approach, that there are no universal truths, which helps promote open-mindedness and prevents ethnocentrism, requires contextual understanding. This would then take us to a moral relativist position, which inhibits social progress.

So, how do we process trauma to go beyond the Aesthetics of Trauma? What are the understood mediums, and for which context? To share a personal anecdote, I attended a retreat composed of a group of BDSM enthusiasts in Germany. A German man met an American woman in Costa Rica from the Midwest and invited her to this festival. The woman had not been to a BDSM retreat prior but was curious. She received a thorough introduction and tour of the entire festival. In the evening, we sat in a space, and she witnessed three people engaged in a BDSM scene, where a woman was tied, and two men engaged in light play involving floggers and rope with the tied woman. At this point, the woman from the Midwest ran out of the space and wailed publicly for three hours. After much consolation, she panicked, “I couldn’t stop thinking, what if that was me?! What would people think of me?!”

From this story, I am reminded of a childhood experience. In my school, we would go live on a farm and do lots of camping for five weeks. During that time, I remembered the difference in treatment I would receive compared to a white girl in my class. When she was ill, she was invited back to the teachers’ home and was fed a proper meal. When I was ill, I was told to figure it out independently. They told me there was “rice in the cupboard. You’re Asian. That’s what you eat, no?”

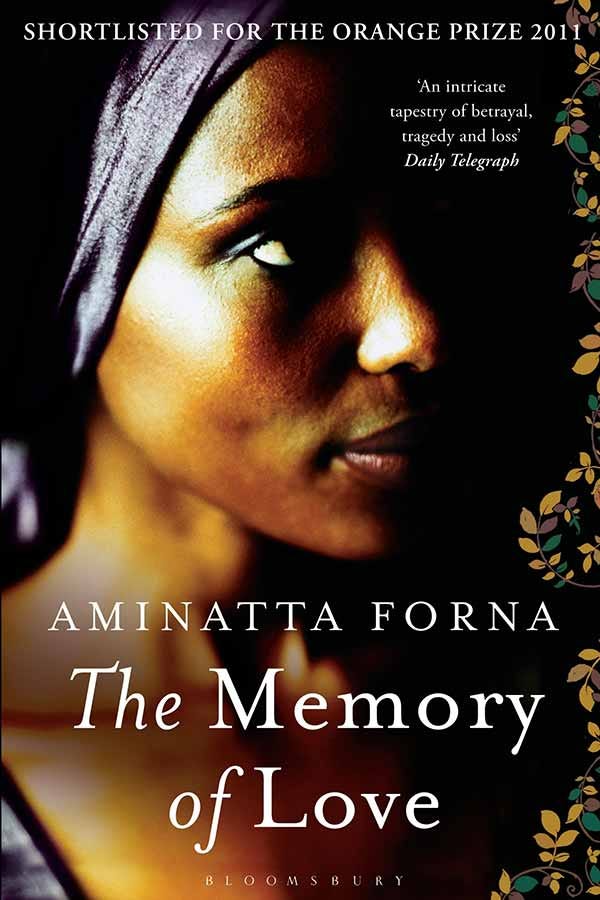

In the text, Stef Craps continues to analyze Aminatta Forna’s The Memory of Love, where Adrian arrives in Sierra Leone to help people deal with trauma, but his Western textbook methods don’t work. I find this extraction from the book Memory of Love pertinent:

‘When I ask you what you expect to achieve for these men, you say you want to return them to normality. So then I must ask you, whose normality? Yours? Mine? So they can put on a suit and sit in an air-conditioned office? You think that will ever happen?’

‘No,’ says Adrian, feeling under attack. ‘But therapy can help them to cope with their experiences of war.’

“You call it a disorder, my friend. We call it life.’ He shifts the car into first gear and begins to move forward. ‘And do you know what these visitors recommended at the end of their report? Another one hundred and fifty thousand dollars to engage in even more research.’ He utters the same bitter chuckle. ‘What do you need to know that you cannot tell just by looking, eh? But you know, these hotels are really quite expensive. Western rates. Television. Minibars.’ He looks across at Adrian. ‘Anyway,’ he continues, ‘you carry on with your work. Just remember what it is you are returning them to.’ (Forna, 2010).

Another quote from the book:

“Hitler, Pol Pot. Funny, isn’t it? How it only seems to be evil people who think they can change the world? I wonder why that is.’ And Kai had responded, ‘Because they’re mad.’ She had dug a sharp elbow into his ribs. Then she shook her head. ‘But they do, don’t they? They do change the world.” (Forna).

The book hints at how Western perspectives have a bias and a “we know best” attitude that often isn’t appreciated, as the insistence on help is often serving one’s own needs more than genuinely helping others.

I will end with a joke popularized by Alan Watts, “Kindly let me help you, or you will drown, said the monkey, putting the fish safely up a tree.”

References

Central Land Council, Australia. (2020). The History of the Land Rights Act. Retrieved 23 July 2020, from [https://www.clc.org.au/our-history/]

Craps, S. (2014). Beyond eurocentrism: trauma theory in the global age. In G. Buelens, S. Durrant, & R. Eaglestone (Eds.), The future of trauma theory : contemporary literary and cultural criticism (pp. 45–61). Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

CriterionCollection. (2014). Slavoj Žižek - DVD Picks [Video]. YouTube.

Duras, M. (Writer), & Resnais, A. (Director). (1959). Hiroshima, Mon Amour [Film]. Argos Films.

Forna, A. (2010). The Memory of Love. Atlantic Monthly Press.

Tarkovsky, A. (Director). (1979). Stalker [Film]. Mosfilm.

Terszak, M. (2008). Orphaned by the Colour of My Skin: A Stolen Generation Story (1st ed.). Routledge.

Weir, P. (Director). (1975). Picnic at Hanging Rock [Film]. British Empire Films.