Mum's been busy writing. She always wanted to be a writer. But she has excuses. It's either because she had me, or she found Buddhism, that's why she couldn't be a writer. The circular logic was air-tight. To write, one needs suffering, but Buddhism helped her alleviate her suffering. Yet she suffers, because she's a mother. Therefore, it's not possible to write.

But since her anuyerism, she has been prolifically writing. When I turned one, it was common in our culture to place the infant in front of the altar, present the child with various items, and observe which ones the child showed more interest in. There would be snacks. Money. Religious artifacts. Pen and paper. I went for the pen and paper. And, oh, how everyone loved that.1

I gave mother the same provisions at her hospital bed. Squishy toys. Ipad. Food. Magazines. Books. Phone. The nurses provided her with tactile objects for the early days. Something to scratch or play with. Different knots. Things to relate back to the world with. The iPad was interesting for a while. Messages to friends. YouTube videos about the end of the world and conspiracy theories (she's really into the one about Japan and the earthquake prediction for July before the hospital). But that didn't last long. Now she writes.

Her prefrontal cortex was flooded with spinal fluid, the reports told me. Executive functions could be permanently affected, the doctor advised: planning, short-term memory. Toilet usage could all become long-term problems. How much of her will remain?

She continues to recover. But with each recovery, new fences are erected. For her safety, of course. Of course.

This week, my appointments are filled with prospecting for nursing homes. As a millennial, without having ever purchased a home, I am instead looking for a room for my mother. At the last place I visited, an angry man sits on the verandah. Screaming. Yelling. The nurse tells me that he is afraid. She tells me that he doesn't remember why he's there. She tells me that the facility is well-fenced. She says it with compassion.

I nod.

Mother is currently a fall risk. She might not be able to handle her drive. She stands, she walks. But the hospital, understandably so, is afraid of her hurting herself.

But what does it mean to keep someone in? Or out? How easily the promise of care slides into the practice of control.

Mother was born into the era of nationalism. The era of control. Of martial law.2 She herself was a tool of state control.3 As a teacher, she instilled much of the nom-du-père.4 She was known as 王老師 (Wáng Lǎoshī)—Master Wang—after all. She was the phallus.5

But she also loved poetry. Tang poetry. Of contradictions. Of love. Of desire. Of death.

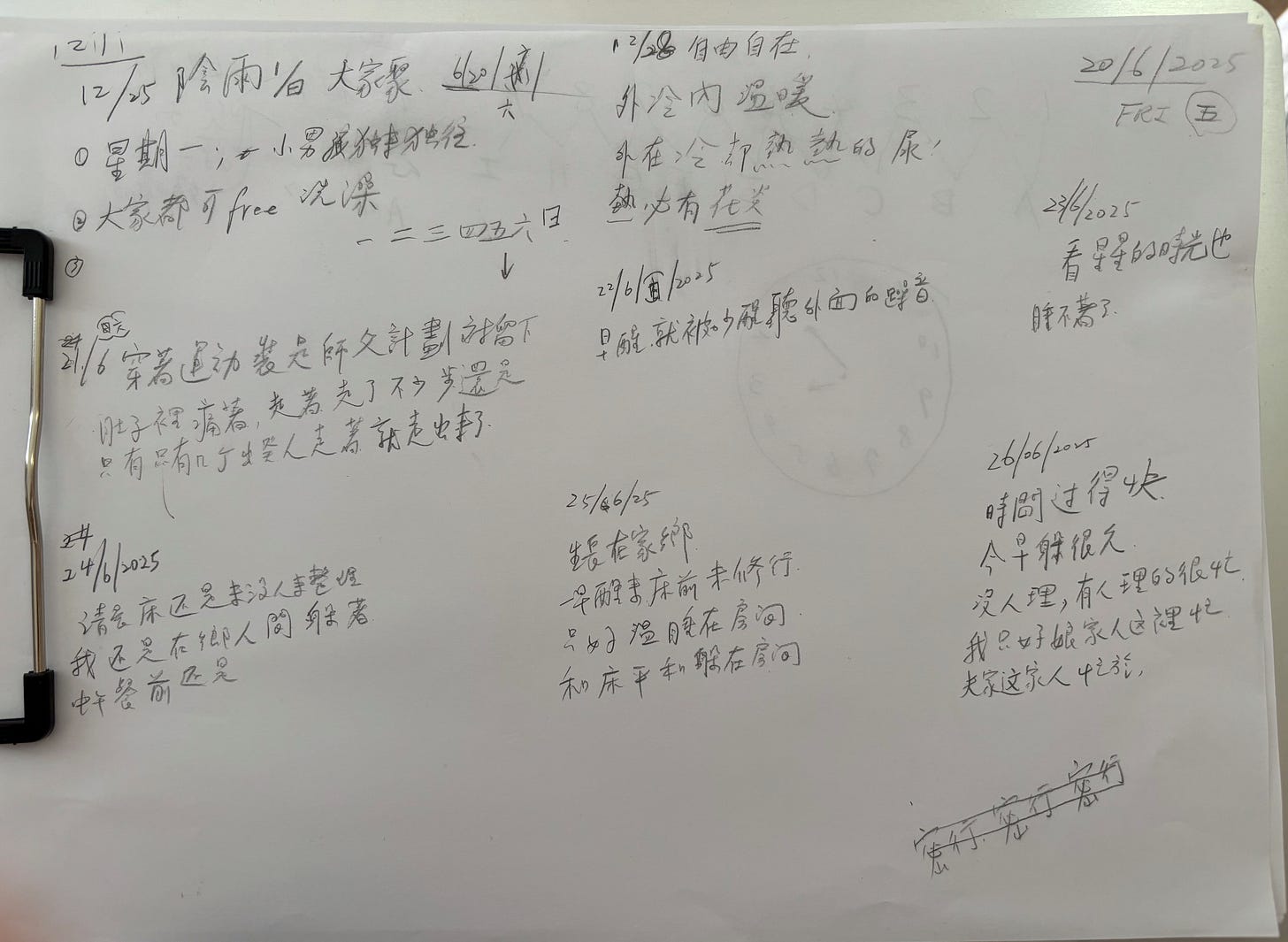

So I prepare for her daily, at her table, with her pen, a clipboard full of blank paper, and her reading glasses. Next to her daily meals. Ready.

She writes. Language comes easily to her. Chiaroscuro. Metonymy. Somatic symbolism. Homophones. Alliterations and phoentic textures. She would often laugh alone because of how fast and overwhelming these ideas came to her, usually faster than her mouth could keep up with. We share this trait. Giggling to ourselves, while everyone else, confused, waiting for explanations that never came.

She writes prolifically. She spent her life teaching others to write. But how often has she written for herself? Now at the hospital, she writes.

Dad showed me one poem she wrote yesterday that caught his attention:

自由自在

外冷內溫暖

外在冷卻熱熱的尿

熱必有花炎

It starts with the phrase, 自由自在, a common idiom meaning loosely, "free and at ease," usually expressing a state of unburdened being, both physically and spiritually. This is also similar to the word for "nature" but denotes a presence that is internal and as is. This freedom, however, is immediately qualified by a shift into the bodily and sensory: “外冷內溫暖” (“cold on the outside, warm on the inside”). The juxtaposition of both literal and symbolic. Public/private, masked/expressive. A conflict between the socially masked and the truth of the drives.

The third line, “外在冷卻熱熱的尿” (“the exterior cools the hot-hot urine”) brings us back to the visceral and the unconscious. The basic, yet intimate bodily function. To urinate on a cold day. The sensation of internal heat expelled into an indifferent environment. Urine becomes a metonym for an embodied expression of discomfort, of urgency, of vulnerability.

Urine not only evokes an elimination but a leakage of internal heat, of passion, of illness, of suppressed desire. She writes, “熱熱的尿” (hot-hot urine), a doubling and intensification. A pressure that demands relief.

Then comes the final line: “熱必有花炎”, literally “where there is heat, there must be ‘flower-flame’.” A poetic key. On its surface, proverbial, implying that heat always leads to blooming or inflammation. But the word “花炎” is not standard. Here, the lack of the prefrontal cortex perhaps releases the ego into a creative portmanteau or homophonic mutation of the usual term, 發炎 (fāyán, “inflammation”), rendered instead as 花 (flower) + 炎 (inflammation/fire). Here, it produces a double register:

1. A literal reading, "heat causes inflammation"

2. A poetic transformation: "heat causes floral flame", a symbolic blooming-through-pain.

The misspelling, or intentional substitution, becomes a site of poetic condensation. Illness is not only suffered, it blooms.

Writing, poetry, is a sublimation.6 A transformation of instinctual or bodily drives into symbolic or aesthetic forms. Urination. Inflammation. Experiences that come with aging. Vulnerability. Here, it requires a negativity that is not denied, nor expressed in shame.7 Something that in our world of positivity and excess, as Byung Chul Han observed, is made impossible.8

The body here is a symptom and a sign. The poem performs a Bionian alpha-function. The conversion of raw, unprocessed beta-elements—the discomfort, the incontinence—into symbolic, speakable thought.9 The suffering is transformed into an image.

The feminine positionality is not of the phallic fantasy of conquest or transcendence. No, it is brought into the intimate, the cyclical, the acceptance. Even in pain, there is flowering. Even in discomfort, a poetic system persists.

The quiet resistance to medical objectification. She reclaims her body in her mother tongue. The registers in which she travels. Not in regression, but a freedom through being, between English, State Chinese, and in Hokkien. She writes in a minotorian tone, within the symptom, refusing capture.10

Of course, there is no escape. No amount of fence scaling, turning off the sensor alarms, or recovery, no amount of persistence, or Chinese medicine, will cure her of her condition. Neither does she demand that. She writes. She does not escape objectification. She disfigures the gaze. Within these lines, within the floral inflammation of her body, the repressed does not simply return, but a deeper sense of knowing otherwise. A knowledge that is not held down by the prefrontal cortex but in the poetics of the drive. In her rearrangements of homophones. In the refusal of instrumental grammar. She sits on her preferred chair, and writes her return, not to childhood, not to her memories, nor State legibility. But to 自然. To 自由自在. Not a Christian freedom of transcendence, but insistence. She writes. She squirts. She blooms.11

This refers to the traditional 抓周 (zhuā zhōu) ritual, a one-year-old’s object selection ceremony practiced in Taiwan and parts of southern China. Objects symbolize future destiny: abacus (finance), brush (scholarship), garlic (cleverness), mirror (beauty), etc. The ritual marks a child's symbolic entry into the world of the signifier—where choice becomes interpreted.

The pen, in Lacanian terms, operates as both phallus and signifier of signification. The child, in choosing it, is interpellated as the symbolic heir of literacy and success. The “love” it generates is not pure affection. It is libidinal, projective, and ideological. It names the child as legible, desirable, productive.

This refers to Taiwan under martial law (戒嚴時期, jièyán shíqī), which lasted from 1949 to 1987—one of the longest periods of martial law in the world. During this time, speech, assembly, and education were heavily censored or surveilled. The Kuomintang (KMT) enforced a Sinicized, patriarchal form of nationalism tied to anti-communist propaganda and Confucian moral regulation. For many, especially state-employed teachers, subjectivity was shaped within this control apparatus.

Teachers during Taiwan’s martial law period were trained and tasked with instilling loyalty to the Republic of China (ROC), obedience to authority, and Mandarin monolingualism—often suppressing native languages such as Taiwanese Hokkien, Hakka, or Indigenous tongues. They were not merely pedagogues but agents of ideological state apparatuses, in Althusser’s sense, enforcing state fantasies of order and continuity.

Nom-du-père ("Name-of-the-Father") is Lacan’s term for the symbolic function that anchors the subject within language and law. It regulates desire by introducing prohibition and structure, often through the paternal metaphor. Here, the mother paradoxically functions as the agent of patriarchal law—a maternal inscription of paternal symbolic authority. This is the reversal that unsettles gendered assumptions of psychoanalytic authority.

“Master Wang” is a direct translation of 王老師 (Wáng Lǎoshī)—a standard Mandarin honorific meaning “Teacher Wang.” However, in this context, it is less a polite title than a symbolic position of authority. The term “phallus” here doesn’t refer to biological sex but to the Lacanian phallus—the signifier of power, completeness, and symbolic mastery. In being addressed as 王老師, she is not simply a woman teaching children; she is bearing the function of the law. She becomes the phallus—not by possessing it, but by being positioned within a system that assigns her its force.

In Freudian theory, sublimation (Sublimierung) refers to the redirection of instinctual drives (especially libidinal or aggressive impulses) into socially acceptable or culturally valued forms—such as art, religion, or intellectual production. Unlike repression, sublimation does not require forgetting or denial; it channels energy rather than erases it. Lacan refines this by suggesting that sublimation elevates an object to the dignity of the Thing (la Chose)—marking it as both desirable and inaccessible.

For Adorno, negative dialectics is where truth emerges not through synthesis but through resistance to positivity, coherence, and closure. In psychoanalysis, this echoes Bion’s notion of “negative capability”—the capacity to tolerate not-knowing, not-understanding, and psychic discomfort long enough for true symbolisation to occur.

Byung-Chul Han, The Burnout Society. Han argues that contemporary neoliberalism replaces external repression with internal compulsion: a tyranny of positivity. The subject is no longer “obedient” but “achievement-oriented,” leading to burnout, depression, and self-hatred when one fails to measure up. In this regime, pain, slowness, and decay are pathologised or hidden. The poem, then, becomes a counter-space of negativity—a refusal to submit to this overexposed, performance-oriented positivity.

In Wilfred Bion’s model, the alpha-function is the psychic capacity to transform beta-elements—raw, sensory, emotional data that are unprocessed and unthinkable—into alpha-elements, which can be dreamt, thought, and symbolised. The mother or analyst often acts as the original container of these beta-elements, digesting chaos into coherence. Here, the poem (and implicitly, the mother-poet herself) becomes her own container, metabolising embodied trauma into aesthetic form.

Hokkien, in this context, functions not merely as a language but as a form of embodied resistance. Suppressed during Taiwan’s martial law era in favor of State Mandarin, Hokkien occupies a marginal yet persistent position—unwritten, oral, intimate, and historically marked as vulgar or backward. When the mother writes in Hokkien, she is not regressing into nostalgia, but asserting a form of freedom through refusal: refusal of institutional language, of medical objectification, of the positivist fantasy of recovery.

This is not a return to innocence but a strategic inhabiting of the minor register—what Deleuze and Guattari might call “minor literature”: a deterritorialized voice that speaks from within dominant structures without being fully captured by them. Hokkien, with its tonal slippages, punning density, and somatic vocabulary, becomes the perfect vehicle for such speech. It is neither purely private nor fully public. It evades translation, diagnosis, and control.

To write in Hokkien from a hospital bed is to reclaim the body not as site of cure, but as a field of poetic expression. The symptom becomes inscription. Not pathology, but poetics. In this act, the mother refuses to be legible to the state, the clinic, or even to the reader. She writes in Hokkien, and in doing so, she writes herself beyond capture.

In classical Chinese thought, 自然 (zìrán) is often mistranslated as “nature” in the Western sense. But unlike the Western concept—which historically posits nature as external, raw, to be conquered or transcended—zìrán denotes self-so-ness, the inherent unfolding of things in accordance with their own rhythms. It is not a passive backdrop or raw material but a mode of being without force—often linked to Daoist principles of non-coercion (wúwéi, 無為) and immanent harmony. Likewise, 自由自在 (zìyóu zìzài) is not the liberal Enlightenment ideal of autonomous will or self-determination over constraint, but rather freedom as ease, as unforced movement, as being-in-flow with the real—desire, decay, contradiction included.

The mother’s return is not toward purity, healing, or transcendence but toward a radical immanence—a blooming that accepts the inflamed, leaky, aged, erotic body without repression. She does not escape objectification; she disfigures the gaze. This is not freedom from limitation, but freedom as situated insistence—a refusal to be defined by function, grammar, or cure. In this way, she embodies a poetics of zìrán, not as romantic return to nature, but as symbolic destabilization of how bodies are read, controlled, and made legible.

Share this post