Being alone has allowed me to contemplate the taste of love, of desire, of hatred, of anxiety. The days are a blur. People ask what I do for work, for a hobby. For god’s sake, don’t tell them about psychoanalysis! I invent things. I play dress up. I drive around. I do rounds at the hospital. Checking in on the sick and dying.

—Talking to you is like talking to a magic 8-ball! She said to me.

I guess that’s better than being called the Prince of Non-Sequiturs—or being diagnosed by a shrink on Betterhelp after 5 minutes, with schizophrenia.

I read about a man once who lived in midtown Manhattan in the 1960s. He would get dressed, suit and tie, pack a lunchbox, and take the lift from his apartment on the 32nd floor during peak hour traffic with everyone. But he wouldn’t stop at ground. No, he’d continue down to the basement. He had discovered a forgotten space there. Once he arrived at his ‘office’, he would take off all his clothes, down to his underwear, then sit at the desk, and write. He’d stay there until the end of the day, then put back on his suit and ride the elevator back up with the rest of the normies. No one was the wiser.

I think about this man often. What stories do we tell ourselves? What fantasies do we maintain? Do we let go of? Do we design? Do we destroy?

—I’m going to an orgy on Saturday. It’s been a few years since I felt the inspiration, I wrote her.

—What sparked the inspiration? She wrote back.

Überdeterminierung.1 What is there to say in these moments? It gets worse as I get older. Memories flood my mind. Is it the effect of psychoanalysis? Mapping and weaving this “tapestry”2 of visions throughout my life. Or is it just me?

In the Mars trilogy,3 as the people get new medical treatments, allowing them to live beyond 140 years old, with the body of a 20-year-old. But their minds? Their psyche is inundated with memories. What are we to do with all these memories?

I’m training to work the suicide hotlines. They train us to reflect. To summarise. To reframe. But is it always possible to see the silver lining? Sometimes, it’s just overwhelming.

Mother’s frontal lobe may be permanently damaged, the medical reports tell us. Father took her to the Chinese doctor for TMC.

—Her qi is imbalanced. He prescribes her some herbs.

I found myself angry.

—No amount of fucking qi balancing is going to help, you fucking quack! I wanted to say.

But of course, I say nothing.

No, that’s not true. I try to burst the bubble of my father. I accuse him of living in Disneyland. He doesn’t get to go yet. I won’t allow it.

He calls the nursing home, the Resort. Today, my mother called me as my father tried to usher her back in the car to return to the Resort. She tells me that they are heading back to Gold Coast. It’s her way of calling for help. Self-soothing. Her loss of autonomy. She never really called me since I left the house when I turned eighteen. To connect. To be witnessed. No, she doesn’t have that need. She’s always been happy living her life. But now, she has suddenly learned how to use her cell phone. It’s a miracle. I find her on the phone downstairs. She sees me appear and hands me the phone like her butler. She tells me that I ought to clean my room, my life from Germany, still half in boxes.

And Gold Coast?4 That was new. Is that where the “resort” of her mind is? Is that her lie? Or fathers? Does it matter? The two of them are conspiring together. Continuing their co-created delusion. And who am I to correct them?

The daydreams we tell ourselves, to keep on sleeping.5

At a recent workshop, a man talked with pain about his fears of the loss of his manhood.

—I’m afraid of being useless. Of not being needed. Of not contributing to anything.

The woman leading the workshop had nothing to say to him. She was more interested in reframing our narratives, towards the wonderous goddess or the mystical feminine. Truly, gender is a construct. But it feels as though humanity is just as much a construct, and no one knows what to do with oneself. It is ever more evident that we are not needed. There’s already an app for that.

A man I once knew in Berlin promotes sex positivity. He’s actually Bavarian, another Bavarian tells me. They somehow leave the oppressiveness of West Germany to live grungy lives in Berlin. Cosplaying poverty. He tells me that it was the way his generation fought against fascism. But did it? Turns out Hitler won. I realised retroactively that I was surrounded by Zionists. I found out that he had performed a vasectomy a long time ago. Suddenly, his sex obsession made a lot more sense.

I think about the bourgeois indulgence prior to each world war. The culture. The debauchery. There’s something similar to the ecstatic people and the Zionists. They listen to the same kind of music. Wordless. EDM. It helps to clear the mind. The horror. The nightmares.

But how does one forget thirst?

“Overdetermination” originates in Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams (1900), where a single dream element carries multiple latent wishes and memories. Louis Althusser later broadened the idea to politics in “Contradiction and Overdetermination” (1962), showing how historical events emerge from intersecting economic, ideological, and political causes rather than a single root.

Freud, S. (1900). The interpretation of dreams (J. Strachey, Trans.). Basic Books, 2010 edition. (Original work published 1900)

Althusser, L. (1962). Contradiction and overdetermination. In For Marx (B. Brewster, Trans., pp. 87–128). Verso, 2005 edition. (Original work published 1962)

Fucking AI has ruined the word tapestry and em dashes. But I’m not going to let them own them that easily!

Kim Stanley Robinson envisions a post-scarcity society where radical longevity leads to psychological overload. Is memory an archive or is it a burden?

Kim Stanley Robinson, Red Mars, Green Mars, and Blue Mars (New York: Bantam Books, 1992–96).

“Gold Coast” carries a doubled colonial echo.

In Australia, the stretch of coast south of Brisbane was marketed in the 1950s as the “Gold Coast,” a developer’s rebrand meant to lure post-war tourists with the promise of sun, leisure and speculative wealth. Its “gold” was never mineral, only the glint of real-estate profit and holiday fantasy.

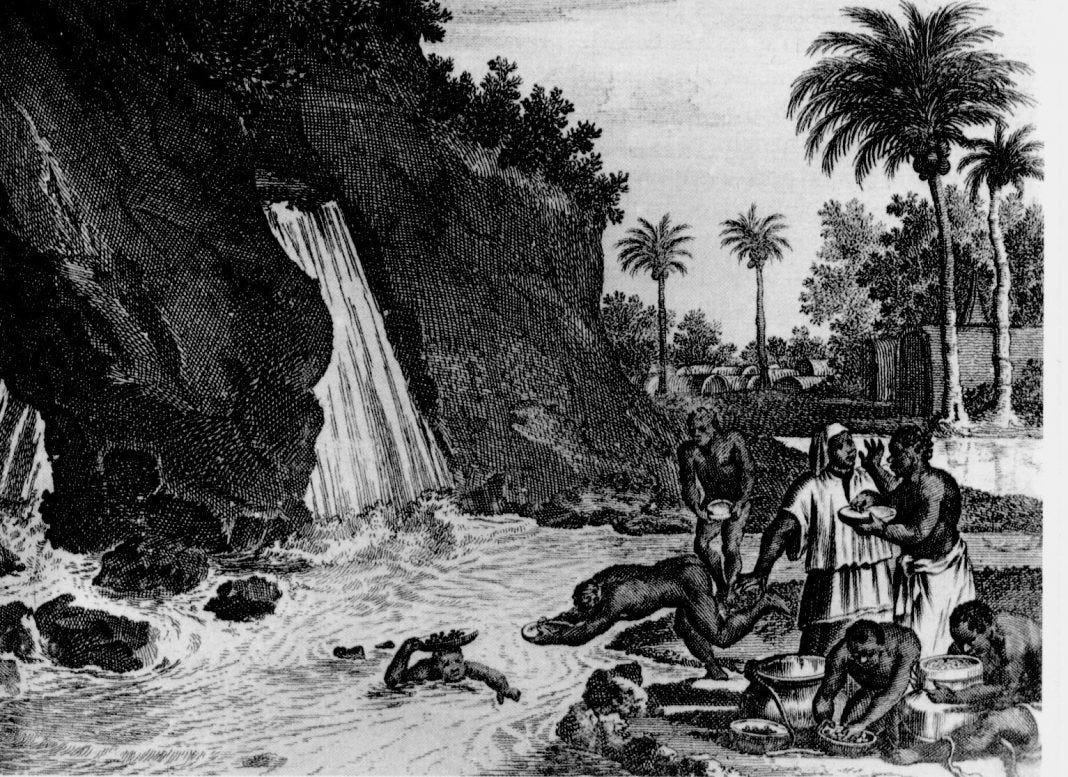

In West Africa, “the Gold Coast” was the British colonial name for present-day Ghana, tied directly to the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century trade in gold and enslaved people.

Across both sites, the phrase began as a sign of extraction and imperial desire; later, it became shorthand for pleasure and escape. In Mother’s mouth, it functions as what Lacan would call an “empty signifier”: a word heavy with historical residue yet unmoored from its origins, a free-floating symbol of elsewhere where suffering can be re-named as vacation.

Australian Gold Coast history

Queensland Government. (2015). A brief history of the Gold Coast. Queensland Government. https://www.goldcoast.qld.gov.au/thegoldcoast/brief-history-of-the-gold-coast-26522.html

Ghana (former British Gold Coast)

McCaskie, T. C. (1995). State and society in pre-colonial Asante. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511563402

General colonial context

Wilks, I. (1993). Forests of Gold: Essays on the Akan and the Kingdom of Asante. Ohio University Press.

Freud recounts the dream of the father whose child has died: exhausted, he falls asleep beside the body. In the dream, the child appears, saying, “Father, don’t you see I am burning?” Words that coincide with the real-world moment when a candle has toppled and the child’s shroud begins to catch fire (The Interpretation of Dreams, 1900, ch. VII). Freud reads it as an instance of wish-fulfilment: the dream tries to prolong sleep by weaving the external stimulus, the smell of smoke, into its narrative until the alarm becomes too strong.

Lacan returns to this in Seminar XI (1964). For him, the “real” breaks through in the burning child’s cry, but the father’s dream itself is an attempt to shield against that real—an image that allows the sleeper to “keep on sleeping,” to delay the encounter with the unbearable fact of death.

Lacan, J. (1973). The four fundamental concepts of psycho-analysis (A. Sheridan, Trans.). W. W. Norton. (Original work published 1964 as Le Séminaire, Livre XI: Les quatre concepts fondamentaux de la psychanalyse)